This Post was co-written by Patrick May of 4dProof

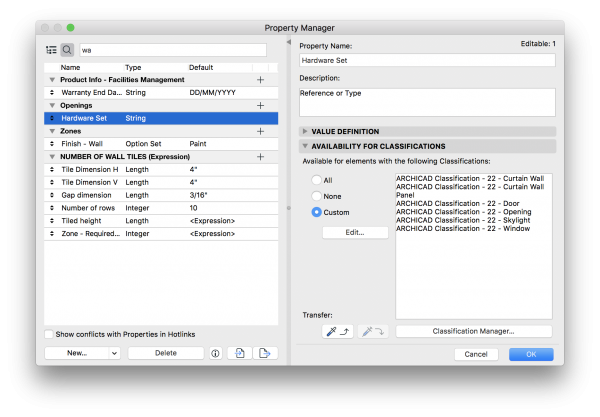

Information Sets in Archicad

We have all read articles and blog posts, attended presentations, and watched videos titled (or about) “Putting the ‘I’ in BIM”. Often these resources talk about leveraging IFC, managing information sets, sending models back and forth, checking model information using programs like Solibri, building specifications or optimizing BIM for post occupancy purposes. Those topics are great, but not always super helpful for everyday use. Some projects are just simple garages, small remodels, custom residences on tight timelines, mixed use projects in jurisdictions with minimal permitting requirements, etc. All have a varying degree of consultant involvement and information needs. Some will argue “it’s not BIM if…(fill in the blank here)”; but all architecture projects fall on a scale of BIM-ness.

If my BIM Execution Plan says that I am going to be coordinating with other consultants via shared models and clash detection will be managed as part of the workflow, I want to leverage as much information as could be needed for a project. If, on the other hand, I am doing a small residential project, where there is still a disconnect between many of the trades and consultants, I will carefully plan out the information that my model gets, applying only what is essential for my documents, schedules, and annotation. That’s not to say I won’t incorporate the IFC geometry from a structural engineer or MEP consultant: just that their information is not as important to me, nor mine to them.

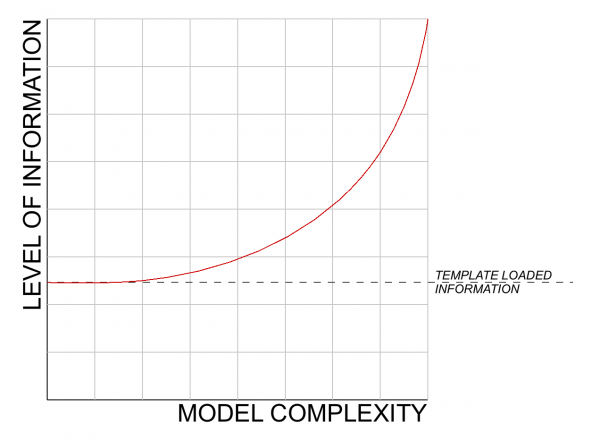

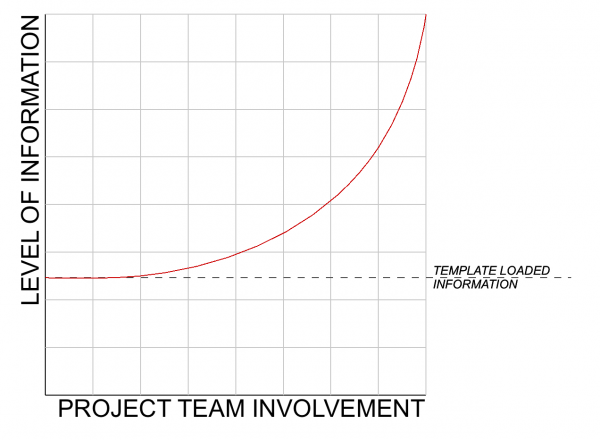

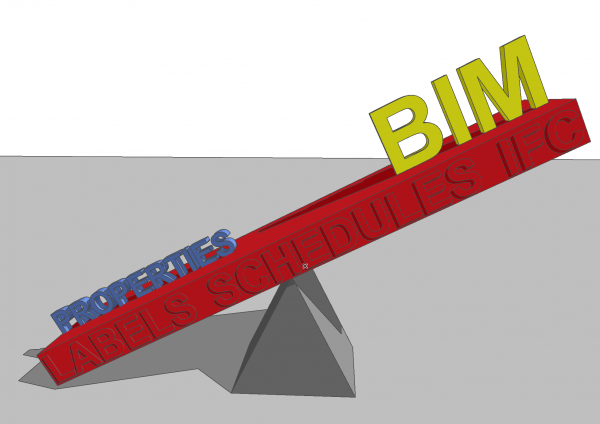

Using a scale like the image above, you can determine the amount of information you need in your model, or in your project as a whole. It is really important to right-size your BIM. The generally perceived attitude is that more information is better BIM. More information is definitely Bigger BIM, or maybe Heavier BIM, but not necessarily better. The information loaded into the model should reflect the needs of the BIM protocols. Essentially, the more you need to get out of your model, or the more consultants are contributing to the model and the process, the more information it may need. This is one of the major stumbling blocks for new ARCHICAD users: knowing when to stop adding information to a model (regardless of if that information is 1D, 2D, or 3D).

Elementary, my dear Watson

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had this notion, or I should say his character Sherlock Holmes had this notion, that a person should not crowd their brain with unnecessary information; it leaves little room for the ‘important’ facts. To Sherlock Holmes, it didn’t matter if the earth revolved around the sun or around the moon; knowing that would only get in the way of his knowledge of the human condition. The human brain is not actually overburdened by information management like this, but a BIM (or the team managing it) can easily be susceptible to information overload.

“you say that we go round the sun. If we went round the moon it would not make a pennyworth of difference to me or to my work.” – Sherlock Holmes

Imagine working on window schedules and stumbling through detailed info such as sealant specifications, fastening spacing, gaskets, framing, headers, etc. All anyone downstream needs is size, u-value, egress, and tempering for a residential schedule. The rest is a waste of time, effort, and therefore money. While not enough information creates extra coordination work on the back, too much information will obstruct efficient modeling and documenting. It’s also a waste if no one is going to use or need it.

This balance of information translates to Archicad usage primarily through Archicad properties. If you are not calling out the weight of nails anywhere in your project, do not include it in the property set. If your windows have six properties that need completing, you’ll fill in the information. If they have sixy properties, odds are you’ll skip it all or forget something critical. Right-sizing model information leads to leaner and more efficient BIM workflows.

From BIM Theory to BIM practice

BIM Information can be any of the following (these are listed in order of importance, according to our opinions—feel free to add in the comments your order, and what we’re forgetting):

- Element Classification

- Archicad Properties

- Element ID

- Structural Function

- Attribute Naming

- Building Material Properties

- Project Information

- Zone Settings and Geometry

- Model Geometry, Element Shape, Size and Location

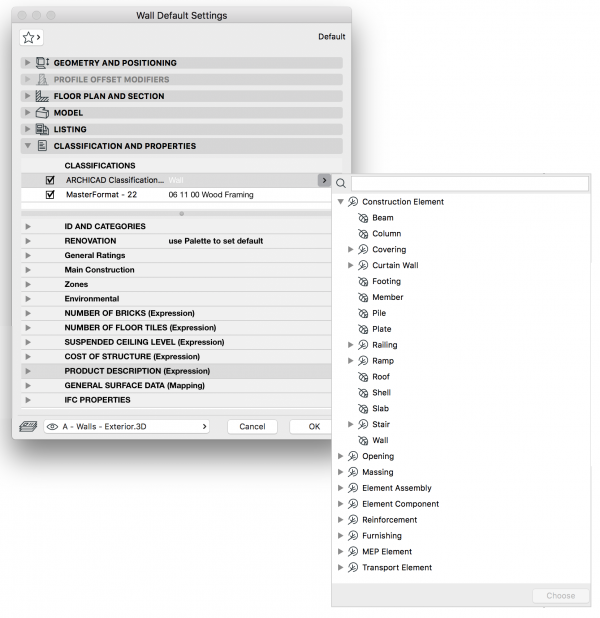

The most important part of applying information to your model is assigning an accurate classification. We now have a range of classification systems to apply to an Archicad model, but the out of the box classification system is one of the easiest to decipher and correctly assign. Classifications are the single most important information source in an Archicad model, and no matter how heavy your BIM needs to be, classifications should be assigned properly.

Classifications define what the element is (rather than the tool name), as well as define the property set (what type of information) that will be applied to the element. Think of the Classification as the sole definer for what an element is. The Wall Tool can be used to model furniture, foundations, landscape elements, beams, screens, etc. A wall only becomes a “Wall” in the world of BIM if it’s Classification has been defined as such. Paying attention to Classifications allows you to control how Archicad interprets elements, and it’s the best way to manage what shows up on a schedule (a window contains elements classified as windows, not solely elements created with the Window Tool).

Next on our list is Archicad Properties. These are really the heart of information in Archicad. Properties only take the back seat to Classifications because, without attention to Classifications, the properties would be a structureless jumbled list that could not be used in any manageable way. The combination of classifications and properties give us an organized list of information that can easily apply to schedules, annotation, model data, and more.

The remainder of information in Archicad can be more or less grouped into file settings or element settings. While each has its unique uses and add value to a project, they are not as easy to leverage on a project wide level for packing appropriate information into your Archicad model. Project information, for example, is applied to the Archicad file, not to specific model or drafting elements in Archicad. This makes it invaluable for listing a consultants contact info or project address, but not for listing specifications or manufacturers of building elements. Element ID and Structural Function are great for IFC exchange, schedule and graphic override criteria, or find and select fields; and I use them every day. But for large and robust information management, they are a small piece of the puzzle, similar to a hard-coded Archicad Property. Attribute naming and application can also be invaluable when managed properly for quick and organized annotation and scheduling. However Attributes lack the level of detail that you can build in an information set centered around properties. That is not to say we should ignore Attribute naming and organization; just that leveraging it as an information storehouse is very limiting.

Information Management Approaches

Ultimately, there are two approaches to managing information. We can pack a model with as much information as possible (front loading properties), and then leverage that model to get the most efficiency out of our documents, schedules, IFC coordination, etc. Alternatively we can carefully balance the information we put into the model with the needs of the project and process (adding properties as needed). Each approach is worth considering, and each can be leveraged for a range of projects. Ultimately, a good template has the information in the properties that will be used in most, or all, projects you will be working on. New properties can be added as necessary for unique project needs.

The goal with information management in BIM is to centralize information and eliminate redundancy. Just like using BIM means you no longer need to check plans against elevations for accuracy and coordination, properties mean you no longer need to coordinate your notes, keynotes, legends, and schedules. It’s automated. If a piece of text is to be coordinated, labeled, and scheduled, it should be managed via classifications and properties. And remember that bolded statement is the goal, not something YOU MUST DO NOW. Figure out where you are on the continuum of automation and work to move towards more automation.

Information and Geometry

There are two parts of BIM, the information and the geometry (the model). Drawings are a mere output. A lot of designers approach a model from a purely geometrical perspective, using the BIM authorship as a design tool and as a way to produce the drawings. A lot of BIM Managers view the model from a purely information management point of view, putting all the focus on project organization and level of information. A wise architect will view each project with the information and geometry sized for its specific needs on a case by case basis.

In some posts, videos, or webinars later in 2019, we’ll dive deeper into this topic with specific examples of how we are using Classifications, Archicad properties, and other types of information on live projects.

Are you following GRAPHISOFT North America on Twitter? Click Here to keep track of all the latest Archicad News in North America (and beyond).

You might also like:

More Articles:

Archicad

Customer Stories

Education

Industry News

Tips, Resources + Downloads

Webinar Recordings